Beanie Babies Flamingo Beanie Babies Platypus Without Beans

On November 5, 1999, Frances and Harold Mountain sabbatum crouched on the floor of a Las Vegas divorce courtroom, divvying up their most valued asset.

Information technology wasn't the house. It wasn't the car. Information technology wasn't the reckoner, the appliances, the jewelry, the books, or the CDs. The hotly contested asset at hand was their Beanie Babe collection.

"Spread them out on the floor," ordered the guess, "and I'll have [you] pick ane each until they're all gone." Frances made a beeline for Maple the Conduct.

At the time, the fiddling bean-filled sacks were more a toy: they were an investment vehicle. Fueled by a rabid collectors' marketplace, Ty Inc. had just exceeded $1B in almanac sales. Certain "retired" characters were going for every bit much equally $13k on the resale marketplace — 3,000x their original cost.

Unbeknownst to the hapless rubes above, it was all about to come crashing down.

How did one man convince the world that these glorified stuffed animals were worth their weight in gold? The answer is tied to our very human nature — and information technology helps explain why nosotros continually autumn victim to speculative bubbles.

Stage i: The creation of a mania

Ty Warner got his start every bit a sales rep at Dakin Toy Company , then the world's largest manufacturer of plush toys, in the early on 1970s.

He quickly became the Dakin'southward top salesman, aided in part by his marketing antics: When meeting with clients, he'd build intrigue by emerging from a white Rolls-Royce, festooned with a full-length fur coat and a cane.

In 1986, Warner had a crazy idea that changed the course of his life.

At the time, virtually plush toys were filled with stiff, rigid cotton. Warner decided that plastic pellets (or, equally he later on called them, "beans") would allow for more flexible, "realistic" toys.

He began to work on his idea on the side — but when Dankin plant out, he was promptly fired. So, Warner decided to launch his own toy company in a suburb outside of Chicago. He dubbed it "Ty Inc."

Initially, buyers told Warner his toys were flimsy pieces of crap. "Everyone called them roadkill," he later on said . "They didn't go it."

But behind the scenes, Warner had a plan up his fur-lined sleeve — and Beanie Babies were about to spark a worldwide mania.

Warner was a master manipulator of supply and need, and he made a series of calculated decisions that drove the market to madness.

Start, he decided to price Beanie Babies at $5 a pop — attainable plenty for anyone to get in on the tendency. More importantly, he merely sold them to small-scale specialty shops and toy stores rather than giant chains, and limited the number they could buy.

Meanwhile, he engineered an incredibly tight-lipped civilization at Ty Inc.: there was a "total information blackout" on things similar how many 'Patti the Platypus' toys would exist sold, or which stores would carry 'Baldy the Hawkeye.'

This created a certain mysticism around the production: Buyers could never observe the whole collection in 1 place, and toys always seemed like they were sold out at each location.

Just, his biggest stroke of genius came in 1995, when he surmised that if he "retired" certain Beanie Babies afterwards a short menstruation of time, information technology would create an illusion of scarcity (in reality, Ty was pumping out millions of them in overseas factories).

After being retired, Beanie Babies that sold for $5 would go for $fifteen-20 — and on the net, some sold for as much as $13k.

Stage 2: Trampled children, smuggling rings, and murder

In the midst of this perceived "shortage," collectors launched an all-out Beanie Infant warfare. Among the more notable instances:

- At a market in Connecticut, fanatical collectors trampled children to go their hands on the retired tie-dye "Garcia" bear.

- A 77-yr-erstwhile Chicago man dubbed the "Beanie Baby Bandit" stole ane.2k of the toys and hoarded them in a storage locker.

- At the border, Beanie Infant smuggling rings ran rampant ("People are smuggling [them] in similar places where they hide drugs," an agent told the Seattle Times ).

- A West Virginia man shot and killed a 63-year-old security guard over a dispute involving "several hundred dollars' worth" of Beanie Babies.

"He didn't desire the greenbacks register — all he wanted was the Beanie Babies," said a Los Angeles store clerk who was robbed at gunpoint for twoscore bears. "With the amount of money these things are getting on the market, it was spring to happen sometime."

During a 1997 promotion with McDonald's, Ty Inc. sold 100m "Tennie Beanies" in only x days. Beyond the country, grown men wrestled over toys with names like "Pinky the Flamingo" and "Seamore the Seal." There were fistfights , theft rings , and temper tantrums.

This mania was great news for Ty, Inc.: By 1998, the company was raking in more than $1B per year in profit. At a vacation party that same yr, Warner, a billionaire in his ain correct, stood before a room of 250 of his employees and shouted , "I've never seen so many millionaires in my life!"

But it was all about to come crashing down…

Phase iii: The Beanie Baby bubble pops

1 night in 1999, Ty announced the retirement of several Beanie Babies… and nothing happened. No market place swell. No value increment. Nothing.

It was the kickoff of the end. Collectors panicked and took to eBay to sell off huge swaths of the toys, flooding the market with a massive surplus of Beanie Babies. Their value, which was contingent on the illusion of scarcity, plummeted.

In a desperate bid to save a sinking ship, Ty announced that all Beanie Babies would go out of production at the end of 1999. It didn't work.

According to Zac Bissonnette, author of " The Great Beanie Infant Bubble ," sales declined by more than 90% — and by the early 2000s, nearly Beanie Babies were worth simply 1% of their original sale price.

BuyingBeanies.com and other bulk purchasing sites sprang up, offer 20 to 40 cents per toy. Once proudly displayed in shop windows, they were sold by the boxful to claw car operators and county fair carnies.

Hoards of hopeful Beanie flippers flocked to toy resellers, hoping to greenbacks in their "rare" Princess Diana bears, just they simply managed to get a few bucks. "They think [the bears] are worth a quarter of a million dollars," one toy buyer said . "No one's ever trying to buy them, only sell them."

The chimera popped, and with it, some big bettors had their little Ty hearts broken.

Phase iv: The family unit who lost $100k

At the height of the Beanie Baby boom, gurus emerged, offering financial insights and words of wisdom to hopeful collectors.

Don Westward, a former wrestling hype man, appeared on Beanie Baby infomercials admonishing viewers they shouldn't "let the opportunity of a lifetime" sideslip through their fingers.

Venerable publications like Mary Beth's Beanie World sold 650k copies per month, and encouraged readers to employ the toys as an "investment strategy," with topics like "How To You Protect An Investment That Increases By 8,400%."

"Simply putting away five or ten of each and every new Beanie Baby in super mint status isn't a bad idea," suggested the Beanie Baby Handbook, in 1998.

Unfortunately, it was — and some people lost a lot of money.

Chris Robinson Sr., an ex-actor from California, spent more than $100k on 20k Beanie Babies betwixt 1994 and 1999, with the idea that the toys would appreciate and ane day fund college tuition for his v children.

"He described it as kind of similar a drug habit," his son, who afterwards made a curt documentary titled " Bankrupt Past Beanies ," told Market place.

He wasn't the only 1: beyond America, thousands of hard-core Beanie collectors — including a New York woman who dumped her $12k life savings into the toys — watched their "fortunes" dwindle

"Information technology'south better than gambling or drugs, right?'' one man said of his family unit's hobby in 1999, in the midst of the collapse. "And we take it nether command now. Nosotros only spend about $500 a month on Beanies."

Simply a question remains: How did otherwise rational, fully-performance adults convince themselves that a $5 bean bag would one solar day pay for a college pedagogy? And why did they buy into an ephemeral trend, even when it was dying right earlier their eyes?

The psychology of a bubble

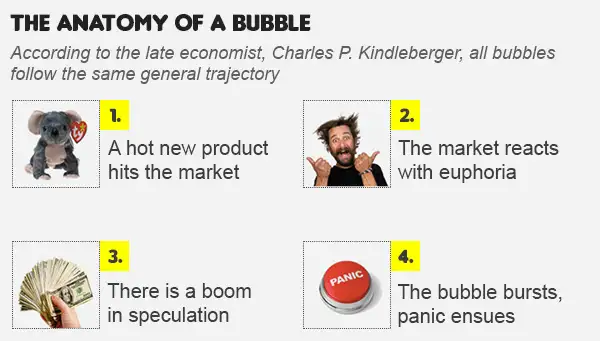

All bubbles — from 1637's tulip mania , to the kickoff dot.com crash, to Beanie Babies — go through iv major stages :

Why exercise we repeatedly fall into the aforementioned trap?

Co-ordinate to economists David Tuckett and Richard Taffler, nosotros often view a hot new fiscal opportunity as a " phantastic object ," or an unconscious representation of something that fulfills our wildest desires.

These objects are "exciting and transformational." They appear to "break the usual rules of life and turn aspects of 'normal' reality on its head." They promise something far departed from the market's typical behavior.

During a bubble, we formulate a "commonage hallucination" of prosperity, and autumn victim to groupthink , a miracle where "a significant chunk of society feverishly buys into a shared dream" and ignores reality.

Eventually, we come up to realize that a $5 bear full of beans is not a sound investment but, in fact, a $5 bear full of f*cking beans , and we self-correct.

Some economists argue this resonates in today's market place.

"Beanie Babies and Bitcoin share a lot of similarities," says Taffler, a professor of finance at Warwick Business School.

Cryptocurrencies, like Beanie Babies, promise a fruitful alternative to classical investments. They are released in express quantities. Gurus extol their virtues, and in online communities, "HODLers" convince each other that they're impervious to the wild fluctuations of a volatile market.

But when a bubble finally pops, says Taffler, "most of us become burned."

In that location was one person who emerged handsomely from the Beanie Baby bubble: Ty Warner.

Bated from getting caught secretly hoarding $107m of his Beanie Baby riches in an offshore Swiss bank account, Warner has kept a low contour over the years — but he's quietly amassed a fortune the size of Djibouti's GDP.

Today, the 73-twelvemonth-old Beanie Baby inventor touts an estimated net worth of $2.7B, good for the 887th richest person in the world. He owns a fleet of luxury cars, a $153m estate, $41m worth of rare art, and the Four Seasons Hotel in New York, where you can hire the "Ty Warner Penthouse" for $50k per night .

Years ago, at the height of his success, Warner told a fellow exec that he could "put the Ty Heart on manure and [people would] buy it."

Turns out, he was correct.

Get the 5-infinitesimal roundup you'll actually read in your inbox

Business and tech news in five minutes or less

Source: https://thehustle.co/the-great-beanie-baby-bubble-of-99/

0 Response to "Beanie Babies Flamingo Beanie Babies Platypus Without Beans"

Postar um comentário